For Zachary Schecter ‘23, it was winning the Most Innovative Game award at the Game Design Showcase his sophomore year that really clinched it: he would become a professional game developer. He watched showcase attendees play his team’s game, Sisyphus, where the mythological main character swings his boulder through 40 levels – from the underworld up to Mount Olympus – and the judges deemed it the best.

“It was a defining moment,” Schecter said. He thought, “I want to do this. I want to do this for a living.”

A longtime gamer, Schecter had considered game design as a career, but the computer science major didn’t know how to make that happen until he discovered the Game Design Initiative at Cornell (GDIAC) program. “It literally changed my life,” he said. “It gave me everything I needed to understand how to make a game and also showed me what the real experience was like.”

Founded in 2001, GDIAC was the first undergraduate game design program at an Ivy League school and one of the first in the country. Students can declare game design as a minor, and Princeton Review lists it among the top 50 game design programs for undergrads.

For many GDIAC students, the showcase is when a passion for game design crystallizes into a career plan – all that hard work rewarded by the intoxicating rush of someone entranced by a game you created.

This year, the showcase was held May 20 in Clark Atrium in the Physical Sciences Building, with almost 600 visitors. According to vote counts, the crowd favorites were the desktop game Munchkey, where a monkey chef defeats dangerous fruit to make fruit skewers, and the mobile game Sunk Cost, a multiplayer stealth game where players are either treasure hunters exploring an underwater shipwreck or spirits trying to thwart them.

“There are a lot of flashy game design programs out there, but we hit above our weight for the resources that we have,” said Walker White, M.S. ’98, Ph.D. ’00, director of GDIAC and senior lecturer in the Department of Computer Science in the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science.

Despite being a highly competitive field, alumni of the program can be found at all levels of the industry, from AAA companies like PlayStation and Oculus VR, to successful indie teams with breakout hits. Not bad for a minor.

Level 1: Origin story

GDIAC originated in the mind of David Schwartz, who was hired as a lecturer in 1999, and is now the director of the School of Interactive Games and Media at Rochester Institute of Technology. His background was in civil engineering, but he had written two textbooks on engineering software while completing his dissertation.

Schwartz admits he didn’t know much about computer science when he arrived, but after a colloquium by Don Greenberg, the Jacob Gould Schurman Professor of Computer Graphics, where Greenberg used familiar physics terms to discuss his computer graphics work, Schwartz realized game physics could be a potential area of study. As the faculty advisor for Cornell's Association of Computer Science Undergraduates (ACSU), Schwarz proposed that, instead of playing games, students could learn to design games of their own.

“I thought the students would find this very motivating," Schwartz said. "Just imagine the passion they would have to make these things.”

While the Department of Computer Science did not yet consider video games to be an academic subject, Charlie van Loan, professor emeritus of computer science and the chair at the time, agreed Schwartz could offer an independent study – but on his own time.

In 2001, Schwartz recruited Rama Hoetzlein ’01, who had dual degrees in computer science and art, and is now an assistant professor of digital media design at Florida Gulf Coast University. He also hired Mohan Rajagopalan M.S. ’02, who later left for the game industry, working on Plants vs Zombies, among other titles.

The trio founded the program and developed the first classes, making connections in the departments of art, music and communication to help students enhance those aspects in their games. Early funding came from a seed grant from Microsoft, a donation from a trustee, and funds earmarked for Uris Library to design a computer lab, which ultimately became the Cornell Library Collaborative Learning Computer Lab.

Schwartz and Rajagopalan finally got permission to establish game design as a minor in 2007, when only a handful of schools were offering undergraduate courses in game design. “Cornell was actually part of the first wave,” Schwartz said. He estimates that almost one-third of computer science majors at the time took his game design course.

Level 2: Training grounds

In 2007, White became the program director. He had started designing games as part of a club in his dorm room at Dartmouth, and had recently published research on how database technology could be leveraged to advanced game design, which enhanced the initiative's academic legitimacy. White envisioned GDIAC as an applied software engineering course for sophomores, where the application just happened to be games.

White runs his introductory and advanced game development courses as studio classes, with students constantly presenting and critiquing each other’s games. Twelve teams of eight – a mix of artists, programmers and a musician – function like an indie game company to produce all or part of a game for the annual showcase. Students not only learn sound design, computer graphics, and software engineering but also the critical art of project management.

While the professional tools for creating games have steadily improved in recent years, the students still build parts of their games from scratch – a decision that White said sets GDIAC apart from other programs. “I'm an educator, and I believe in teaching foundational, portable skills,” White said. “I want them seeing how everything fits together.”

In addition to the showcase, students have frequently competed in juried festivals, such as the Boston Festival of Indie Games, but mainly before the COVID-19 pandemic. The program’s biggest breakout hit was the mobile game Family Style – a party game where players pass ingredients between phones to assemble dishes. In 2019, the game was featured on the front page of the Apple store, went viral in Thailand, and reached a peak of 15,000 daily active players, White said.

But despite the preparation GDIAC provides, game development is still a tough field, with stiff competition for jobs, grinding hours, and frequent layoffs. “I love supporting my students who want to go into the game industry, but I don't sugarcoat it,” White said. He sends five or six graduates off to the game industry each year, while 15 to 20 others go on to work in game-related tech. “I make sure people are going in wide-eyed, because they're hopefully in it for the long haul.”

Level 3: Achievements unlocked

Developing video games may seem like child’s play, but it’s a big business. The Entertainment Software Association reports the U.S. spent $56.6 billion on video games in 2022; worldwide, the market was estimated to be worth $214.2 billion. About two-thirds of people in the U.S. play video games at least once a week, and the industry employed more than 400,000 people in 2020.

“It's definitely a challenging industry; the bar is generally really high,” said Rajiv Puvvada '10, an early graduate of the program and industry veteran who has worked at top companies, including Zynga, Juicebox Games, and AWS for Games. Especially for entry-level positions, “there are only so many of those spots that come around,” he said.

Puvvada can’t remember a time when he wasn’t gaming; there are photos of him reaching for a Nintendo controller from his high chair. He started making games as a teenager, “going about things in the entirely wrong way,” but he felt the stigma that game development wasn’t a “real” job. Through GDIAC, he discovered a path to the career he wanted.

Working in a multi-disciplinary team with deadlines at Cornell was excellent preparation for the real thing, he said, and learning the fundamentals has helped him stay agile as gaming technology evolves. “The game industry field is very wide, and it changes a lot, often very quickly,” he said.

Puvvada said he’s always happy to talk with current students and help them enter the industry and grow their career. He thinks this is vital for “increasing the level of diversity in the industry, because that's something that benefits all of us.”

There are no cheat codes for breaking into the industry, but recent graduate Kristina Gu '21, M.Eng '22, said after multiple attempts, she felt fortunate to have landed an internship at PlayStation. Thanks to a good word put in by her internship supervisor, Gu is now a technical designer at Naughty Dog, an affiliated company behind the critically acclaimed game The Last of Us.

GDIAC made her well-rounded, which makes her a more flexible game designer, she said. “Game development is really one of the only fields that has that perfect balance of being interdisciplinary, technical and creative, which is something I really, really enjoy.”

A long-time gamer, Gu became captivated by game design while playing Uncharted 4, another Naughty Dog title, in high school. She’s been a rabid fan since.

Even Gu’s parents are largely happy with where she’s at. “My dad is still holding out hope that maybe I’ll go back to business school, but I think they’re pretty happy with how it’s gone,” she said.

The End: And another quest begins

After graduation, Schecter will be the latest GDIAC alum to join the game industry, with a position developing graphics at Blizzard Entertainment. He interned at the company in 2022 after being selected from a pool of about 20,000-30,000 applicants.

“I love Blizzard games. I actually run the Overwatch team at Esports at Cornell, which is a Blizzard title,” he said. “I’m sure that helped.”

Schecter will once again descend to the underworld to work on Diablo 4, the fourth installment of their popular Diablo series – a set of dungeon crawler games, where players contend with hordes of demons.

Soon, Schecter’s games will not only be played by hundreds of people at the game design showcase, but will captivate millions of people around the world.

Patricia Waldron is a writer for the Cornell Ann S. Bowers College of Computing and Information Science.

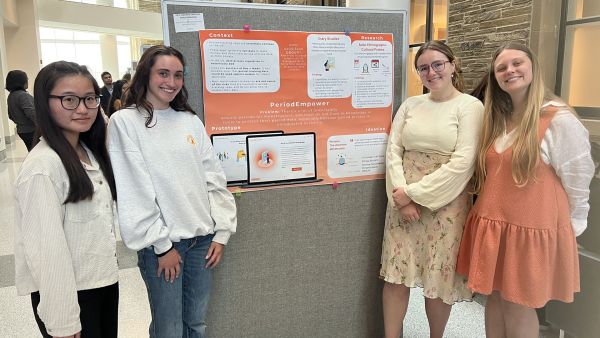

According to one student team, millions use menstruation tracking apps, though there are serious privacy concerns to consider when logging such sensitive data. Alexandra Pultorak, Olivia Rodriguez, Emily Sine, and Jacqueline Woo presented “PeriodEmpower,” an educational platform to equip people with knowledge and tools to protect their period data. The team took home the “Social Impact Award.”

According to one student team, millions use menstruation tracking apps, though there are serious privacy concerns to consider when logging such sensitive data. Alexandra Pultorak, Olivia Rodriguez, Emily Sine, and Jacqueline Woo presented “PeriodEmpower,” an educational platform to equip people with knowledge and tools to protect their period data. The team took home the “Social Impact Award.”